GEDDES AS TOWN PLANNER

Although Geddes is today best known as a town planner, he did not start off that way

FIRST STEPS : DUNFERMLINE

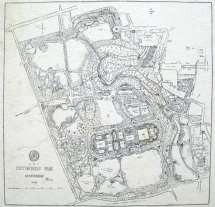

In 1903 Andrew Carnegie bequeathed about half a million pounds to his home town for the establishment of a trust fund to be administered by twenty representative citizens. The trustees were charged to bring into “the monotonous lives of the toiling masses of Dunfermline more of sweetness and light” and they commissioned two men, Patrick Geddes and architect T.H. Mawson, to report separately on the best way to use the 70-acre Pittencrieff estate as a recreational and cultural amenity. This was the first town planning assignment Geddes had received and it provided him with an opportunity to put his developing theories of civics and sociology into practice. He began characteristically with a detailed personal survey of the town, drawing ideas and information from a variety of sources but, perhaps because he was unsure of himself in this new role, he also sought the advice of specialists in different fields before proceeding to write his report. The range of his proposals, published in a 230-page document entitled City Development, A Study of Parks, Gardens and Culture Institutes, probably exceeded the brief, however, Geddes did begin on a practical note advising on waste disposal, drainage and the utilisation of existing resources. Photographs and drawings juxtaposing the “actual” and the “possible” illustrated his recommendations in detail while the overall plan envisaged the park as the social centre of the whole town catering for various interests. As one would expect, nature study figured prominently with ample provision for botanical and zoological gardens, but Geddes adopted an equally didactic attitude towards the “Culture Institutes” in line with the 19th century paternalism which advocated improvement through education. The Concert Hall, the Art Institute and the History Palace were conceived in a traditional style of historicism, monuments to the edifying power of culture, like the museums erected in every major British city after 1851. The trustees were somewhat taken aback but did not take up the proposals of either man.

Elevations

Pittencrieff

TOWN PLANNING EXHIBITIONS

“A torture chamber” to those expecting a perfected vision of the future was how Patrick Abercrombie described the Edinburgh Room at the Town Planning exhibition of 1910. “Within this den sat Geddes … talking about anything and everything. The visitors could criticise his show — the merest hotchpotch — picture postcards — newspaper cuttings — crude old woodcuts — strange diagrams — archaeological reconstructions … many of them not even framed”. This account of Geddes’ first major excursion into travelling exhibitions gives some indication of the kind of material that he used and the way he displayed it. Describing himself as a “visual”, as opposed to an “auditive”, he placed greater emphasis on the ideas expressed by the pictures than the requirements of elegant presentation. “Scrappy” though it undoubtedly was, the Edinburgh Room and the Cities Exhibition that evolved from it established the city as a central object of investigation, the sociological unit of a complex community. It was also very successful in the popular sense and continued the theme of interpretive exhibition centres which had originally appeared in the Outlook Tower and the Dunfermline report. Geddes, however, had a much grander scheme in mind. The immense “Index Museum” which he proposed was to have been an “Encyclopaedia” displayed and organised on a rational plan as a “material expression of the evolutionary order of things.” It remained an unrealised dream at his death.

Dublin Exhibition Catalogue

Cities Exhibition 1910